Time in the dataARC Tool

How do you think about time? When you open up a search engine to explore the circumstances pertaining to when something happened, do you type in a set of calendar dates, the name of a cultural period, or perhaps just the description of an important event in time?

An example of a temporally-specfic query is the eruption of the Samalas Volcano, which is hypothesized to have influenced the onset of the Little Ice Age, and took place in 1257 CE. The answer likely depends on your main area of study and your disciplinary background. Different disciplines and their specialists have developed an astounding variety of systems for dividing up time and describing it. This poses a real challenge for any interdisciplinary project, including dataARC.

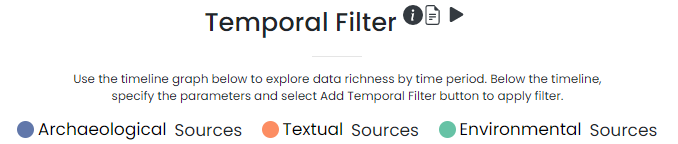

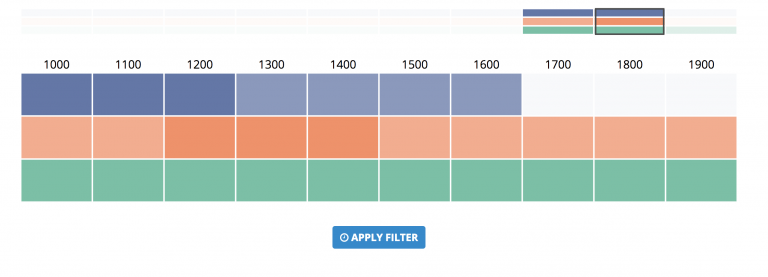

The dataARC project brings together archaeological, environmental, and historical data from across the North Atlantic region, creating a dataset that captures processes, events, and experiences across nine countries over thousands of years.

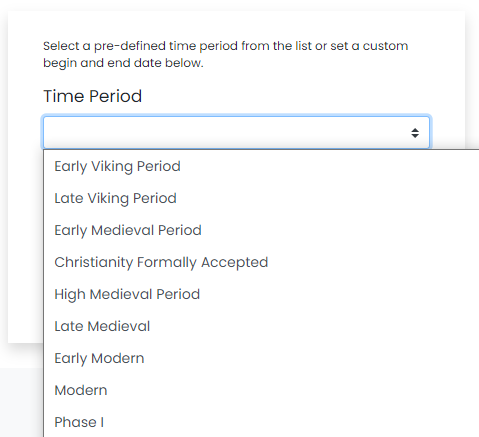

While some of our data describe long-term processes, other data describe discrete events or rapid changes, and inevitably the creators of each dataset have their own way of dividing up time and talking about when things happened. Paleoenvironmental datasets often refer to geological time scales, archaeologists talk in terms of cultural time periods, such as the Early Viking Age, whose cultural definitions vary from place to place, and historians name years and months.

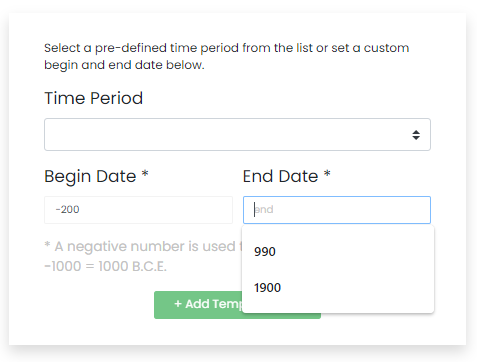

The difficulties with time go beyond disciplinary divides, reflecting specific meaningful choices made by the creators of each dataset. In dataARC, the dates listed for the Icelandic Sagas are the Sagas were written down and the dates to which the Sagas may refer. An Icelandic Saga may be speaking of the initial occupation of Iceland dating to the mid 9th century, but was written down in 1300. We have, effectively, Saga Dates and Saga Event Dates. While the Saga data refers to the recording time as well as the time of the event, dates for archaeological remains are the best interpretations of their time of use in the past, based on both relative and absolute dating techniques.

These different ways of dividing up and thinking about time become important when designing a tool to search across data that have irreconcilable differences in their conceptions of when things happened. It’s the irreconcilable differences, the incredibly persistent lack of agreement between research communities, that are the heart of the problem. There is no concrete agreement about the Early Viking Age in Greenland in calendar dates, and even less agreement about whether a particular historical date that falls near the beginning of a geological era should be considered “close enough” for its events to be studied as part of that era. While there is no universal standard, and this project doesn’t pretend it can create and popularize one, we can define and publish our own rules that are used to translate different ways of describing time.

To this end, we will use Period.O to make our internal rules publicly and persistently available. Period.O helps us define and reference how we link across the varied ways the creators of different datasets think about time. This allows us to maintain a flexible structure, with each dataset documented in a way that reflects its own disciplinary conventions and the character of the data but also supports integration. In dataARC, time is a flexible concept.